I had an art Trifecta when I visited Chicago last week. I saw a comprehensive Cezanne exhibit at the Chicago Art Institute, its premiere museum. I saw at the Museum of Contemporary Art, a museum that often disappoints, a large show of installations and sculptures of Nick Cave, an artist coming into prominence, and I saw in a hole-in-the- wall gallery in a developing neighborhood, an artist that I had never heard of. What they all had in common was the accessibility of the art. The friend I was with said you could take a pre-teen to the Cave show and the child would get its intricate hangings and the monumental outre statues, knowing some to be a joke and others just dazzling, but wondered whether the visitors would get Cezanne, and I thought so, even if Cezanne is known as a great artist and people might see the show just so as to say they were there.

Remember that accessibility was not so long ago was not regarded as a virtue. Modernism was elite art in that it was expected to be appreciated by only some, painters and writers requiring their readers and viewers to work hard to make sense of what was presented. That was true of Joyce and Kafka and also of Picasso as well as of Cubists and Surrealists. Jackson Pollock had to explain that art, as in his Abstract Expressionism, did not require meaning, any more than did a field of flowers, even if I do insist that Rothko is philosophical in that he presents patches of color, which means color before it is taken into being a thing that has color, and that the discontinuities of Elsworth Kelly show how the nature of experience is also discontinuous and not just pieces of colored shapes set next to one another. Indeed, a criticism made to me of Impressionism is that it is so pretty that there is no intellectual challenge in engaging it and so it is the style of art that people most readily to which they introduce themselves. But accessibility is now back in fashion, brought back, I think, by the plain, homesy prose of World War II war correspondents and so are like the Eighteenth Century paintings of beer barons in England and flirtatious women in France.

Here are three Cezanne paintings not included in Chicago but so very famous that they are the touchstones of his style and meaning. One is “Mont Sainte-Victoire”, from 1887, a subject Cezanne often portrayed in varying shadows and shades, and so akin to Monet’s renderings, again and again, of the same cathedral seen in different lights. What is even more striking and quizzical is that the tree in the left foreground is clearly focused, to use a modern term, as is the arched causeway in the remote right, while other parts of the painting are assemblies of blotches, barely in definition: the mountain in the background a pattern of shades of color, and the fields in front of it also patches of green interspersed with yellowish buildings known mostly for their box like shapes rather than their details. This is the not hidden secret: the viewer goes back and forth from boxes and gobs of paint to seeing things and so the viewer discovers or invents for his or her self that art can be abstract, about its materials and shapes rather than just a botched representationalism. The viewer invents abstract art even if not having mastered why it is that Cezanne decides which patches are things rather than unfocused though I suggest it has to do with the real objects framing what is airy and fluid. He is making so many multiple decisions about what to identify as objects and what not to do so that I can’t catch up.

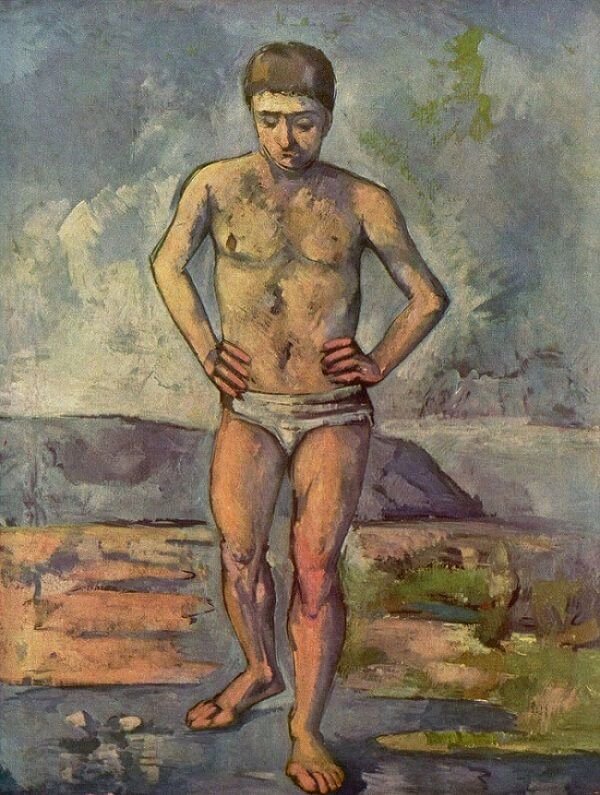

Another famous and approachable picture is Cezanne’s “The Bather”, from 1885. As a portrait, it is unusual because it uses frayed and darkened edges so as to distract the painting from being a realistic picture into being an abstracted one, but in fact what is striking as fresh and new is the realism of the figure itself. Those dark blotches on the bathing torso are not just patches of dark to obscure the person. Rather, they are disfigurements or birthmarks that make the person all too human, ugly blemishes far removed from the Greek ideal of perfect beauty. Moreover, those blotches do not symbolize a moral disfigurement as might be found in Shakespeare, but just what a real body looks like, both men and women having been weathered by nature or nurture into being their other than ideal forms. That you notice the bather for what he is departs from Ingress or other painters who also depict people of other than perfect form but nonetheless gussied up well enough by their clothing and in their faces so as to be socially and aesthetically pleasing. So Cezanne is showing the unseemly even without the shock of nudity as is to be found in Lucien Freud, but shocking enough to be unpalatable, a message received as offered whether or not also sensed as revolutionary, which it is indeed, not because of politics, but because, in Impressionism, the naked female figure is breaking those own bonds of convention, a revolution that will go on for a century and a half, until art nudity no longer remains as thrilling and contrary to convention, just how people can look when undressed.

Another great accomplishment that is easy enough to understand even if it is a transitional picture between realism and abstractionism is Cezanne’s “The Large Bathers”, still unfinished at the time of his death in 1906, and perhaps his greatest accomplishment, not those pictures of apples that the Freudian Meyer Shapiro remarked as offering sensuality which is reading a lot into bowls of fruit. “The Large Bathers” has an arrangement of nude figures that make up a ballet pose infused with movement. But what Cezanne accomplishes is not a transitional figure between real and abstract figures but a wholly realized one in that the abstractions of related shapes also carry as well the distinctive features of each of these nudes. Some of the women are fatter than others, some lithe and slim, each one asking to be inspected for their particular shapes, their individual natures, and not just their ensemble presentation. How can a woman be both singular and of her type? An eternal mystery that asks a contemplation of how each of them are to be contrasted to each one of the others. That is as deep as it gets unless one looks at the total separateness of a woman as in Vermeer's “The Girl With the Pearl Earring”. This is doing something different: finding commonality and difference.

Nick Cave is approachable because he is sensational, dazzling viewers with his ever fecund installation of hanging and shifting decorations the size of postal cards. Children would find that marvelous and diverting even if not classifying it as art except if pointed out to it as such even if in contrast to framed windows into reality that have defined art since medieval times, Cezanne a part of that older tradition, however much, as I suggested, Cezanne varies focus, something not done before that. Cezzane, we might say, is silent and contemplative while Cave and much of contemporary art is loud and crashing in its effects, such as the hanging from the rafters of automobiles crashing into one another that was a trope of early contemporary art. And if you look at these individual hanging panels, spinning in the wind, Cave shows himself fecund in that there are so many different objects he offers: one an op ed psychedelic glimmering and altering visual space, another a kaleidoscopic way of change occurring within the object, and another akin to an embroidery. Nor are these objects descended from Calder, whose constructions are spare and balances the forces of wind and attraction and repulsion of its parts, and so properly thought of as abstract art, but rather distinctive one from the other so that the viewer is immersed in the midst of those different things. That installation alone is worth the price of admission as spectacular.

Cave, however, also does something very different. He makes figures out of macrame or fabric, the materials all different but similar to one another, what Cave calls “Soundsuit”, in that each is sort of like a person, clearly recognizable as shod feet and with legs, but with thorsos attended to because of the materials and heads that are often not there, just ending without faces but just elongating the torso into a conehead type shape, some of them flowery, some of them textured, each one fresh as if they had a personality rather than a shape somewhat human appreciated because of its plumage and material, and so overcoming the claim that a person inhabits the object rather than the object being itself aside from the hidden self, that reduced to nothingness. A child could play with these fantastic creatures as beyond being a human creature and so beyond Bert and Ernie or any other form of puppeteering.

While Cave is playful, he is also serious especially, as the placard notes say, his original constructions were in tribute to the events concerning Rodney King. Perhaps Cave’s most moving presentation is that of a darkly colored tree that extends out of a man’s feet but rather than ending even conelike and so a semblance of humanity, ends in branches of trees without a head above the trunk that replaces the torso and would allow a tree to be something like a person. Rather than there being a connection between humanness and a tree, a very old metaphor, there is a root, the feet, that arises into emptiness and only nature itself, a concatenation of branches that makes the object eerie and depressing rather than the joyfulness which so many of his other objects invoke. As Cave says himself, he wrings joy and pleasure out of the dark parts of racism, and so he attempts many emotional tones, not just the ironies often found in other contemporary art. Cave is doing what Bisa Butler did for me at the Chicago Art Institute what I had seen in Chicago more than a year ago, which was tremendously ornate and textured clothing on Black street kids that for a moment persuaded me that there might be a fresh flowering of fashion though, to my disappointment, I don't find it either in the East or the Midwest or in the Mountain states, but only drab clothing, uninventive , muted colored tops for both men and women, and both sexes wearing cargo pants. Nobody dresses up any more and I was referred by those in the know to examine Byzantine clothing, which were colorful and elegant, rather than what we have today. Ah me. John Singer Sargent made women glow even if the men did not have elegance, only acceptability. (I wish Vanessa Friedman, who writes on fashion for the New York Times, would comment on the whys and wherefores of the drab when artists are making more spectacular fashion.)

Roman Villarreal is a lifelong Chicagoan of Mexican heritage who expresses images and things from the point of view of his community. His work is accessible for two reasons. He is not so original that his art challenges our perceptions of art forms or art images and because he is working in styles that will be meaningful to the community he sees as his audience. So his collective portraits of his figures are of Hispanics who wear mustaches and usual clothes and a bronze skin tone and characteristic facial features though he also does not portray eyes in some of their faces, perhaps to indicate that they are figures rather than people, or to make them anonymous, or for any other reason where the lack of eyes has become a stylistic feature that has by this time become a cliche rather than a striking image. In “The Rainbow Lounge”, in particular, the assemblage of people includes dresses that are broadly or even primitive in their drawing and seem to be painted on wood planks so as to emphasis its ethnic authenticity, a picture of the people in what is not their natural habitat but rather in what seems to be their natural representation. The same is true of his elongated paper creation of a kind of statue without a face, reflecting also Cave doing without faces and insead using objects where faces would be. So this is I think now a familiar sense of what a sculpture is, which is not a portrait of what people are really like, but a presentation of how people sport themselves, recreating themselves as a splash whereby the inner craving can be displayed in their exteriors, exaggerating aspects of life and mixing them with things to make that point that a self is a display.

Once in a while, Villarreal makes a keen observation. He presents a torso of a woman who has dumpy breasts and nothing alluring about her pubis, which violates Courbet’s “The Origin of the World’ which makes the pubic area strange and exotic and very accurately depicted and Villarreal is also contrary to ideals of Greek art, but in keeping with the Cezanne tradition, perhaps precursored by Goya, of people presented as warts and all. This is an insight of Villarreal but hardly an innovative one, and it is pleasurable to see this perception trotted out as a valid insight into life, but it does not confound the viewers very much and so can be readily adjusted, which is what happens when art adjusts to perceptions of art so as to move it along but only slowly and being absorbed into the ever unfolding cultural consciousness even if art critics will properly mainly focus on art that is jarring our perceptions, making us accommodating by requiring us to see things anew or ever more exact than was the case hitherto.There are many ways in which art can serve.