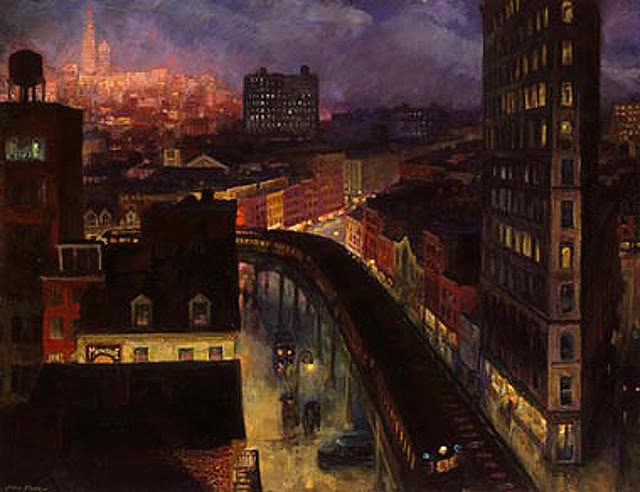

John Sloan’s well known painting “The City From Greenwich Village”, painted in 1922 and now hanging in the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D. C., is a prime example of the Ashcan School, called that because it focused on the grimy realities of city clutter and constant construction and the working class people who lived there. The painting remains striking because it provides a distinctive and very American view on the nature of city life, one quite different from the idea of urban life found in British, French and German presentations of city life. James Whistler takes London bridges and turns them into swathes of dark color on a dark background to create paintings that are forerunners of Rothko. Cezanne fills the wide boulevards of Paris with crowds of people. Ernst Kirchner and other German Expressionists portray a Berlin crowded with strange looking people enjoying the nightlife. Sloan emphasizes, instead, how important is the physical aspect of cities, both the architectural structures and the architectural infrastructure. Spatial relations are more important than ethnicity or crowd psychology in explaining citylife.

Sloan picks an angle high above the city to provide a vantage point that allows him to look directly into Greenwich Village while also panning up enough so that he takes in the relatively remote well lit district, perhaps the entertainment district, that is in the distance. There are so many layers of slightly off kilter vertical slabs that one might think one were in a Cubist painting, but these are the walls of buildings as well as the straight streets that intersect with one another at odd angles, as anyone familiar with the Village will know is still the case. Connecting the farther removed parts of the city to the Village is an elevated train that can indeed be described as serpentine in its movements, even if that is an old cliche, because it is the only thing that moves in curvy lines through a city of straight lines angling off from one another both horizontally and vertically.

Sloan decides to portray New York City at night and so shows off how cold and uninviting are places that do not have electric illumination, and so captures how scary is an imperfectly illuminated city. The train cars produce their own light and so are beacons of humanity amidst the darkness. The center of the picture is to the left and below the central point of the canvas. It is the light that arises from the streets of Greenwich Village without showing the stores or signs which are producing the light. Rather, what the picture shows are the walls of the buildings that are blocking off that light. That includes brick walls with advertising painted on them and buildings, one like the Flatiron Building, and so new at the time, where many of the windows are lit, which suggests that it is a residential rather than a commercial building, because the buildings in a commercial district would be dark at this time of night.

Another feature of the experience of cities that Sloan portrays is that the architecture is a jumble of styles, buildings from long ago right up against buildings of recent construction. This is different from a suburban development, where all the homes went up at about the same time, as well as different from a utopian community where all the buildings are of the latest style and so coordinated, or else a medieval village where all the houses are similarly ramshackle, as can be found in any number of Dutch landscapes. Rather, buildings of different styles and textures provide context for one another and so New York is an immediate experience of time travel, moving a walker between cast iron construction to Twenties Romanesque to glass towers within a block or two or even on the same block. This is an experience true in all cities, though perhaps never more than in Rome, where the effect is dizzying, a walker invested in so many times simultaneously. Sloan depicts that experience in “The City From Greenwich Village” by presenting earlier Nineteenth Century brick buildings next to a later Nineteenth Century building with an angled roof behind which is a “modern” office building with big windows and a water tower on its flat roof, all across from, on the other side of the elevated track, that modern apartment building, and in the distance a big building not connected to its surroundings. Such juxtapositions are still the way it is.

All of this information adds up to a sense that the city is very specialized, that neighborhoods are not ethnic enclaves but change if you move just a few blocks and so become surrounded with a different set of buildings and light patterns that may not be familiar to you. The connection between these places are the streets and the elevated trains, there not being any cars or cabs around to make any of the streets depicted feel inhabited, the light coming only from places not otherwise depicted. And this is indeed the quality, the experience, of urban life: it feels very isolated and lonely unless you are involved in something, especially at night, when so many parts of the city are abandoned.

So what is a city? It is not so much a set of people as a set of spatial relationships, each area of the city performing a distinct or reiterated service, the whole of it connected by its roads and its trains. The city provides the infrastructure of buildings and transportation connections that allow people to be productive. Badly described at the time as a beehive so as to celebrate its activity, the city is better described as an engine that produces everything from dry goods and meat distribution to entertainment for its residents, that made possible by the proximity of its residents to one another.The structure of the city is there for the residents and visitors whether or not they are there themselves. Unlike other Ashcan artists who fill their pictures with throngs of pedestrians, as George Bellows does in his “New York” and in his “Cliff Dwellers”, Sloan, in this painting, gives you only a few people walking the streets under umbrellas and only the suggestion, rather than the depiction, of people in the elevated car and down among the lights. What he is therefore able to convey is the overwhelming presence of the city itself. The structure of the city as a receptacle waiting for people to make use of it still remains the case, as Amazon has demonstrated once again recently by deciding to settle its new headquarters in New York because isolated campuses just aren’t as synergistic as are densely populated cities that already have universities producing computer scientists and an entertainment infrastructure that would make of a city a pleasant place in which to work.

So what Sloan captures is what has always been the cosmopolitan city from at least Babylon on: bustling, mysterious, interconnected, a place with a distinctive look and character. But as time moves on, Sloan’s picture is also a work of history that displays what the city looked like and felt like at a specific time, one that has passed on and which we cannot even look at with nostalgia because the people who lived in that city are all dead. It was another time, one in which illumination came from clusters of light bulbs of small wattage and all casting a yellow rather than a natural light. It was a time before neighborhoods were created on a model, which meant before Rockefeller Center and Hudson Yards. It meant that a startling and vivid feature of the city architecture were the elevated trains, which remain in operation in Queens and downtown Chicago but no longer take up space above most of Manhattan. There were few cars in the streets in Sloan’s time when now there are few ebbs in traffic. Then, Greenwich Village was inhabited by artists and its narrow and crooked streets remain as they were, but Greenwich Village now has very high priced real estate, and so has a different population. A viewer shifts back and forth when contemplating this painting between its particular time and the universal processes it portrays, and that is enough to justify the judgment that this painting, as well as the work of other Ashcan artists, is significant.